♻️ A Repeatable Pattern for Custom Domains on AWS

Using CloudFront, ACM, Route 53, and Infrastructure as Code

Adding a custom domain to an application often sounds trivial. In practice, once you introduce multiple environments, centralized DNS ownership, and automated delivery pipelines, domain management becomes one of the more subtle sources of operational complexity.

Over time, I've converged on a repeatable pattern for managing custom domains for static and frontend-heavy workloads on AWS. This post describes that pattern at an architectural and workflow level. It is not a step-by-step tutorial, but a set of design principles and boundaries that have proven reliable, scalable, and low-drama across multiple applications and environments.

If you are responsible for both application delivery and organizational cloud hygiene, this pattern can help you keep responsibilities clean while still enabling fast iteration.

The Core Problem

At a high level, custom domains touch several concerns at once:

- Content delivery (e.g., CloudFront)

- TLS certificates (ACM, with regional constraints)

- DNS ownership and records (Route 53 or equivalent)

- Multiple environments (dev, stage, prod)

- Cross-account boundaries

- CI/CD automation

In practice, this creates a simple but important tension:

CloudFront lives with the application. DNS lives with the organization.

Trying to collapse these responsibilities into a single account, stack, or toolchain tends to produce:

- Overly broad IAM permissions

- Fragile cross-account trust relationships

- Hard-to-audit DNS changes

- One-off exceptions that age poorly

The pattern below embraces this separation instead of fighting it.

The Pattern at a Glance

This approach assumes:

- CloudFront distributions are owned by application accounts

- DNS is centrally owned in an organization or root account

- Certificates are requested by application infrastructure, but validated by the DNS owner

- Infrastructure is split by scope. In this setup, CDK is used for application infrastructure, while Terraform is used for organization-level resources such as Route 53 and identity/SSO, where I've found the tooling and workflows smoother for cross-account and organizational concerns

- CI/CD automates everything after an explicit one-time boundary

Conceptually:

Application accounts own:

- CloudFront distributions

- Origin resources (e.g., S3 or application backends)

- ACM certificates (requested in the required region)

- Deployment pipelines

Organization/root account owns:

- Route 53 hosted zones

- DNS validation records

- Alias records for custom domains

DNS resolution crosses account boundaries, but DNS ownership does not.

Architecture

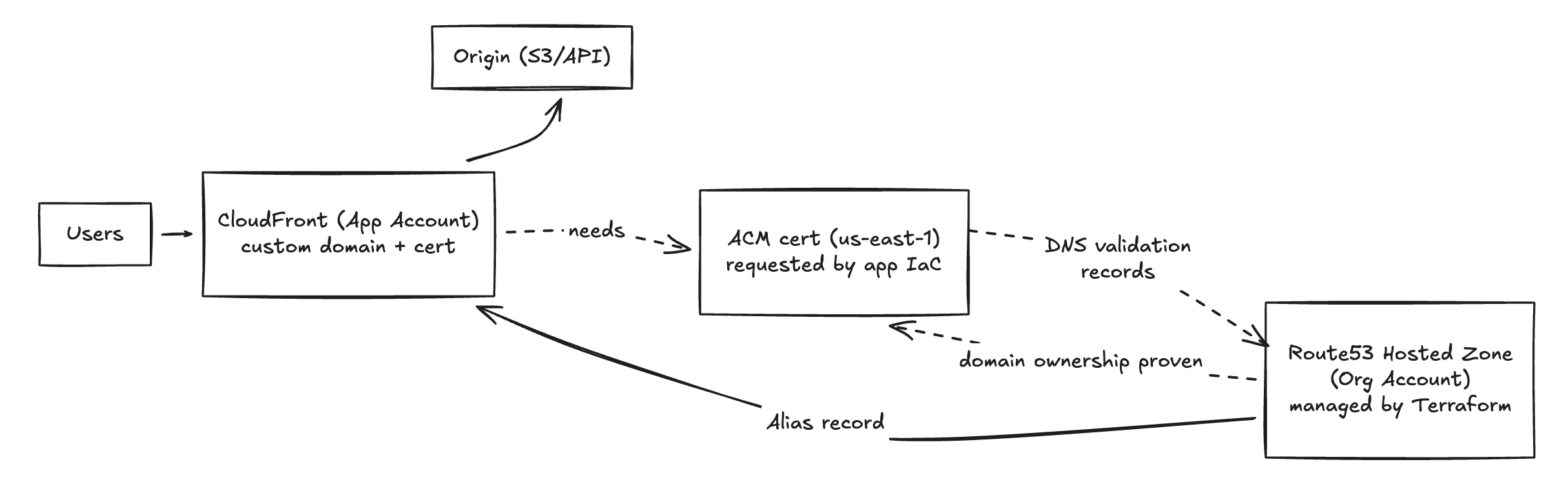

The diagram above shows the boundary and the request flow:

- Users hit the custom domain; CloudFront (application account) serves the traffic.

- CloudFront uses an ACM certificate requested by the app's infrastructure (must be in

us-east-1). - ACM emits DNS validation records; the organization-owned Route 53 hosted zone gets those records.

- Once domain ownership is proven, ACM issues the cert.

- The hosted zone has a stable alias record from the custom domain to the CloudFront distribution.

- CloudFront talks to the origin (e.g. S3 or an API backend).

The split is deliberate: CloudFront and certs stay with the application; DNS stays with the organization. That one-time contract (app requests cert and validation data; org proves ownership and controls DNS) is what makes later deployments routine.

Why Split Infrastructure Tools?

It is reasonable to ask: why not use a single IaC tool everywhere?

In practice, the split here is not primarily tool-based. It starts with separating repositories and ownership boundaries.

Different layers of the system have different ownership models:

- Application-scoped infrastructure benefits from living alongside the application code and deployment lifecycle. This keeps changes close to the teams that own delivery and operations.

- Organization-scoped infrastructure (such as DNS and identity) benefits from being centralized, tightly controlled, and decoupled from any single application's deployment pipeline.

This separation creates a clean, auditable contract between application teams and the organization.

Trying to grant application stacks cross-account permissions into organization-level DNS or identity systems introduces:

- Wide IAM blast radius

- Hard-to-review changes to critical shared infrastructure

- Increased risk of accidental outages

Once those ownership boundaries are clear, tool choice becomes an implementation detail:

- CDK is used for application-level infrastructure, where tight coupling to app code and pipelines is a feature.

- Terraform is used for organization-level resources such as Route 53 and identity/SSO, where cross-account and organizational concerns have proven easier to manage.

By splitting first on ownership and scope, and only then on tools, responsibilities stay explicit and permission models remain tight.

The One-Time Manual Boundary

This pattern introduces a small, explicit manual boundary per environment:

- The application infrastructure requests a certificate.

- DNS validation records are extracted.

- The organization-owned DNS stack proves domain ownership.

- The certificate is issued.

- The resulting certificate reference is stored securely for automated use.

After that:

- CI/CD deploys CloudFront distributions automatically.

- DNS alias records remain stable.

- Re-deploys become routine and predictable.

The philosophy is simple:

Make sharp edges visible once, then automate everything around them.

This creates a clean, auditable contract between application teams and the organization.

Domain Naming and Environment Isolation

A secondary benefit of this pattern is clarity in domain naming.

Each environment gets an explicit, predictable domain structure:

- Development environments use subdomains

- Staging environments mirror production shape

- Production domains remain clean and stable

This enables:

- Independent deployability

- Safe testing of TLS, caching, and edge behavior

- Clean teardown and recreation of environments without DNS churn

Each environment is independently deployable, testable, and disposable.

Operational Benefits

In practice, this pattern produces several operational advantages:

- Safe migrations – CloudFront distributions can be replaced without destabilizing DNS

- Clear blast radius – A broken application deploy does not take down organizational DNS

- Fast iteration – Application teams can ship without waiting on org-level changes

- Auditability – Domain ownership, certificates, and DNS responsibilities are explicit

- Scalability – The pattern scales cleanly as the number of applications and environments grows

Why This Fit My Setup

This pattern wasn't designed in the abstract. It evolved within the constraints of my setup:

- CloudFront at the edge

- Multiple environments per application

- Centralized DNS and identity

- A strong preference for clean, safe, efficient, automated redeploys

Having repeated this pattern multiple times now, it has become my default.

Final Thoughts

This is not the only way to solve custom domains on AWS. However, it is a pattern that prioritizes:

- Clear ownership

- Explicit trust boundaries

- Consistently repeatable operations

The real win is reducing cognitive load and deployment anxiety by making domain management predictable.

Takeaway

Treat DNS and application infrastructure as separate concerns with a clean contract between them. The resulting system is easier to reason about, easier to audit, and far less likely to surprise you later.

- v1.0.0 - Feb 12, 2026